Advance directives help you express what matters most to you. Learn why it’s critical to let your loved ones and doctors know your wishes regarding end-of-life care.

Imagine a serious illness or accident left you unconscious or mentally unable to make decisions about your health care. Would your loved ones be able to speak on your behalf? For example, would they know:

- If you’d like doctors to preserve your life as long as possible?

- If you’d like to be buried or cremated?

- If you’d like a chaplain to visit you at end-of-life or officiate your funeral?

- Who should be your “health care agent,” the person you’d choose to communicate with your doctors on your behalf?

Research shows one-third of health care agents experience long-lasting negative feelings like stress or guilt because they do not know their loved one’s wishes, according to a 2011 study in Annals of Internal Medicine. You can reduce this burden on your loved ones through advance care planning.

“Advance directives increase the chances that people receive medical care that is aligned with their values and priorities.”

How can I make my end-of-life wishes known?

You can help ensure your loved ones and health care providers carry out your wishes by completing forms called advance directives.

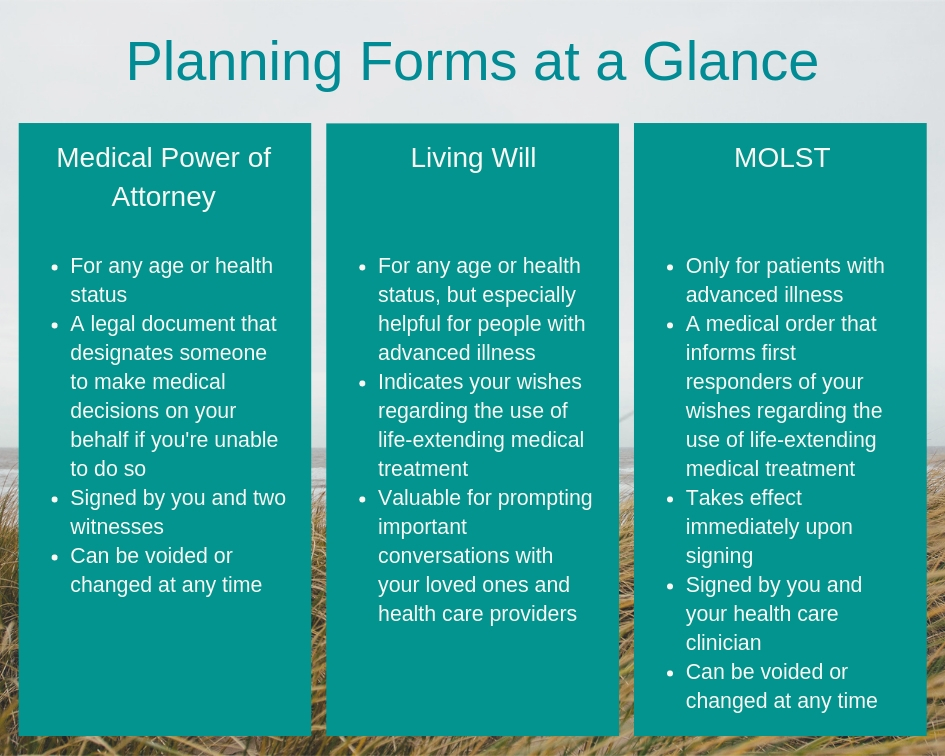

Advance directives include forms—the medical power of attorney and the living will—that document your wishes regarding medical treatment you would or would not like to receive at the end of life.

“Advance directives increase the chances that people receive medical care that is aligned with their values and priorities,” explains Jennifer Ritzau, MD, director of palliative care and medical director at HopeHealth. “It allows their voice to be heard at a time when otherwise it might not be.”

You don’t need to be sick to complete advance directives.

Why should I complete advance directives?

By filling out advance directives, you give loved ones solid information about what type of care you’d want, so they can feel confident about making decisions on your behalf.

“If there hasn’t been this planning process, family members can be thrust into an uncomfortable spot of having to decide on medical care for somebody they love very much. You can end up feeling very guilty about the decisions that get made—[it’s] ‘coulda, shoulda, woulda,’” says Dr. Ritzau.

You don’t need to be sick to complete advance directives. In fact, it’s good planning to have advance directives in place even when you’re healthy.

And if you or a loved one is living with cancer, dementia, heart disease or another serious, progressive disease, advance directives are especially important.

Creating advance directives is about more than paperwork. Rather, it is meant to spark important conversations with your loved ones and health care providers. Through this dialogue you can:

- Understand your health condition more deeply

- Designate someone (a medical power of attorney) to make decision on your behalf if you are unable to do so

- Reflect on your values and wishes

- Communicate those wishes to your agent and health care providers

“It’s that tight union of input from the patient and the family, and input from the medical team, that really allows for good cohesive medical decisions to be made,” explains Dr. Ritzau.

What is a medical power of attorney?

A medical power of attorney, or health care agent, is the authority you grant someone to make medical decisions on your behalf if you are unable to do so.

Your health care agent can be anybody—a partner, adult child, best friend, clergy member or neighbor. The person should understand your wishes and be comfortable communicating with your doctors. View the power of attorney for Rhode Island and Massachusetts.

“It’s that tight union of input from the patient and the family, and input from the medical team, that really allows for good cohesive medical decisions to be made,” explains Dr. Ritzau.

What is a living will?

A living will is another legal document that lets you state your wishes about health care if you lose the capacity to communicate your wishes.

Think of a living will much as you would a birth plan or even travel itinerary. This is a document that lets you express how you want to be treated – or not treated – in the event you cannot communicate these wishes yourself.

Dr. Ritzau recalls one patient who wrote in her living will, “If you’re reading this, something horrible has happened,” and proceeded to share her love of nature and Bach.

“As a result of this fabulous living will, we were able to honor her wishes even though she could not express them herself. The document did the talking for her,” Dr. Ritzau says.

Once you complete a living will, share it with your family members and primary care provider. Keep a copy in a safe place at home and let your medical power of attorney know where it is.

Health conditions are complex and can change. It’s not realistic to predict future circumstances and document every possible scenario in a living will.

In fact, the legal status of living wills varies greatly by state. Massachusetts does not recognize living wills, while Rhode Island provides a document similar to a living in its Durable Power Of Attorney For Health Care form, page 3: Part II: Health Care Instructions. Given the variability, the conversations often provide more value than the forms themselves, says Dr. Ritzau.

What is a MOLST form?

Different than the living will, the MOLST (medical order for life-sustaining treatment) is only for someone who has a serious illness. It is a medical order, not a legal document.

A MOLST takes effect immediately upon signing. It documents the decisions you make with your doctor regarding life-sustaining treatments, such as resuscitation or intubation.

MOLST forms are usually bright pink and displayed over a bed or on a refrigerator where EMTs are trained to look for them.

Like advance directives, MOLST orders are reversible, and you can request and receive medical treatment at any time, regardless of what the MOLST indicates.

Learn more about Rhode Island MOLST or Massachusetts MOLST.