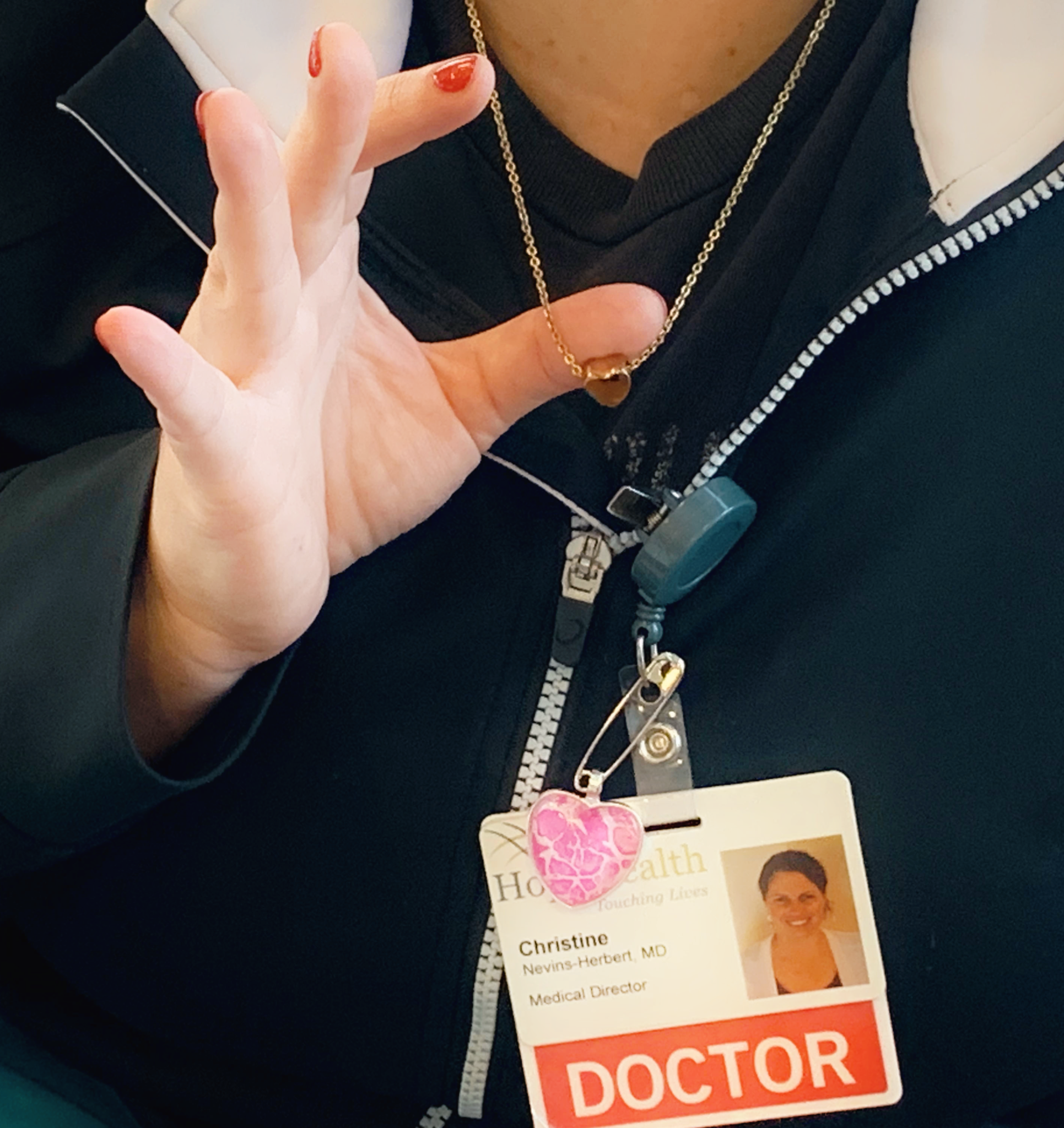

Dr. Christine Nevins-Herbert carries her dad with her every day on her rounds at the HopeHealth Hulitar Hospice Center.

“I have a little bit of him in here,” she says, gently touching the small rose-gold heart at the end of the 20-inch chain around her neck. January 11 marked the first anniversary of Nevins-Herbert father’s passing.

Losing him made her see her job differently and added a new layer of understanding to what the families of her patients are going through.

“Everybody’s experience is their own and I would never tell somebody ‘I know exactly what you’re going through,’” Nevins-Herbert says. “But I get it on a different level now.”

Losing her dad has also changed the way she looks at one of the most routine tasks of her job as a HopeHealth medical director providing hospice and palliative care.

A phone call in the middle of the night

John Herbert’s death four days before his 74th birthday happened suddenly in the middle of the night. Her dad was still working, running the home heating oil company his father founded and was on the rebound from a recent shoulder surgery.

Nevins-Herbert was supposed to drive from her home in Providence to Connecticut to see him later that Saturday to attend a University of Connecticut women’s basketball game in Hartford. But at 1:30 in the morning, she was getting into her car to make the 2 ½-hour drive to Stamford Hospital, where he had been taken after his heart stopped beating.

She had been awakened by a phone call from her younger brother, who lived with her parents in Darien. Her brother told her their dad wasn’t feeling well and put him on the phone. Her dad told her his throat felt funny and he was having trouble taking deep breaths. He thought it might be his anxiety. He seemed alert and not in any immediate danger. She encouraged him to relax, take some sips of water, focus on his breath.

And then her dad collapsed and her brother was calling 911 on the home’s landline. In the harrowing minutes that followed, all Nevins-Herbert could do was listen helplessly as her brother started CPR and then her dad received defibrillation from a police officer who arrived with an automated external defibrillator about five minutes before EMTs did and took over.

“I said to my brother, ‘Don’t let them take him until I get there. I need to see him.’”

“I’m hearing it charging, I’m hearing it shocking,” she recalls. “I’m hearing my father die is what’s happening.”

Her mom put the phone to her dad’s ear while first responders worked on him. Nevins-Herbert encourages family members of patients in her care to talk to their loved ones even when they seem like they are unconscious. She believes hospice patients who may not seem responsive can still hear and may understand.

“I told him I loved him. I told him c’mon you can do this and if you can’t it’s okay,” she says.

Nevins-Herbert was still on Route 95 South in Rhode Island when her brother called to say their father didn’t make it. She had to pull over and collect herself.

“Then I got back in the car and kept driving,” she says. “I said to my brother, ‘Don’t let them take him until I get there. I need to see him.’”

She arrived at the hospital around 4 a.m. and got to see her father. The death certificate was already completed.

It stated her dad died from a cardiac arrest, a vague and problematic cause of death, and that he had been a smoker.

“It could have said cardiac arrest of unknown etiology,” she says. “There was no right way to fill it out but what bothered us was the smoker thing because he hadn’t smoked since before I was born.”

Permanent record of the fact of death

A death certificate is an official legal document declaring the cause of death and the location and time of death. It is needed for settling estates and other uses.

Death certificate data informs state and national mortality statistics used by public health officials to determine which medical conditions receive priority for research and development funding.

But a vast body of research shows death certificates are often inaccurate. A study published in March 2020 in the journal Clinical Medicine and Research found 85% of death certificates completed between 2013 to 2016 at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics had at least one error and 51% had more than one.

A death certificate must be filed within a specified time. In Rhode Island, physicians must complete and return the medical part of a death certificate within seven calendar days of the date of death pronouncement.

“I take an extra second to make sure it’s done properly, that it’s done thoughtfully. That it’s not just, done, whatever, good enough.”

An ‘extra second’ to get it right

Nevins-Herbert says her father’s death has made her more mindful of the importance of this routine task for physicians.

“I know the impact it can actually have on the family and this is going to be a legal document that they’re going to have for the rest of their lives,” she says.

“I take an extra second to make sure it’s done properly, that it’s done thoughtfully. That it’s not just, done, whatever, good enough.”

Sometimes a cause of death is obvious and sometimes it’s unclear. If it’s the latter case, Nevins-Herbert says she sometimes checks with families to see if they have a preference for the language she uses.

It’s an opportunity her family didn’t have, she says.

Looking back, she is thankful the end came quickly for her dad and he didn’t suffer. Her family was fortunate the pandemic was still two months away. Over 300 people attended his wake. John Herbert’s ashes were spread on the golf course he loved, off the deck of his family’s Florida condo, on his cemetery veteran’s marker and in the Atlantic Ocean. And Nevins-Herbert saved some for her little heart-shaped urn necklace. Her mother has one too.

Her father was always there for her. He still is.